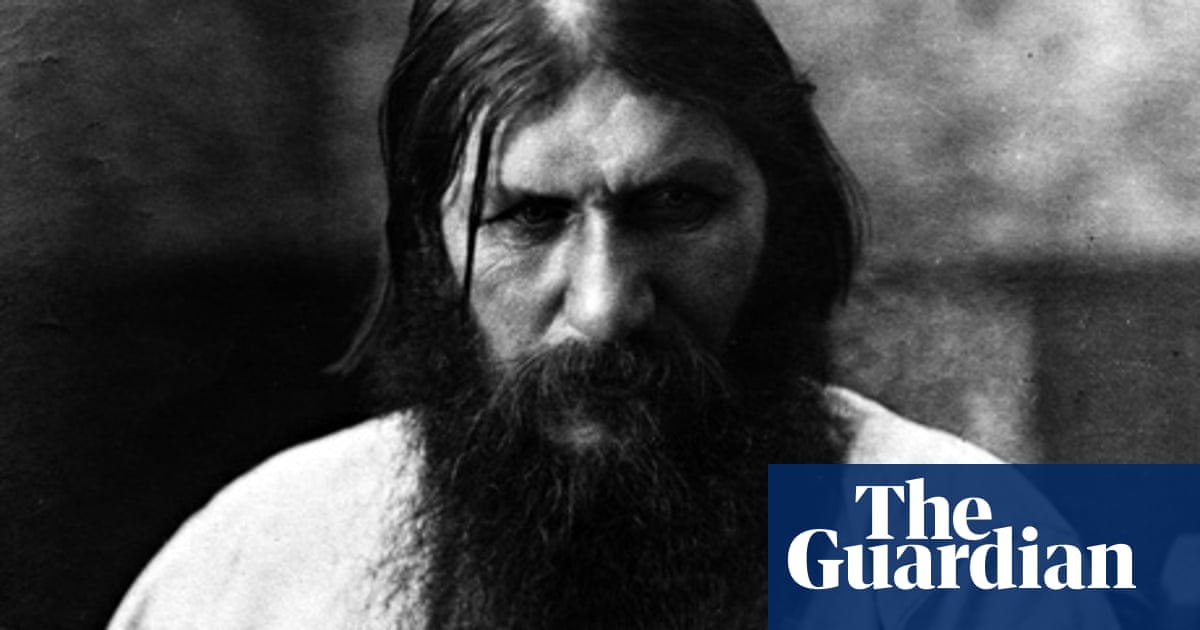

Rasputin

Russia is the world’s largest country by area, and it has a history to match. Test your knowledge of Russian (including Soviet) history with this quiz. Although he attended school, Grigori Rasputin remained illiterate, and his reputation for licentiousness earned him the surname Rasputin, Russian for “debauched one.”. Rasputin Music is the largest independent chain of record stores in the San Francisco Bay Area. Founded as 'Rasputin Records' in 1971 in Berkeley, California, Rasputin has grown to operate seven locations around the Bay Area and three locations in the Central Valley cities of Modesto, Stockton and Fresno. Shop for CDs & DVDs.

The death of Rasputin has been a subject of fascination since the hour of his murder due to his stubborn, nearly superhuman refusal to die.

Wikimedia CommonsThe death of Grigori Rasputin has inspired endless fascination for over a century.

Grigori Rasputin’s death was as difficult as the times he lived through, much of which he had a direct hand in creating.

It reportedly took several doses of cyanide and two fatal gunshot wounds to finally put down the Mad Monk of Russia, the spiritual guru to the Tsar and Tsarina, a man widely feared as the power behind the throne of the Russian empire in the final stages of its collapse.

From Mystery To History: Grigori Rasputin’s Rise To Power

Wikimedia CommonsGrigori Rasputin in a Russian Orthodox monastery after his religious “awakening.”

Born in 1869 in relative obscurity to a peasant family in Siberia, Grigori Rasputin didn’t show much inclination to religion early on. His spiritual awakening came after visiting a monastery at 23.

Though he never took the holy orders, he rose to prominence as a mystical religious figure; more like an Old Testament prophet than a Russian Orthodox priest.

Dressed in dirty monk’s robes and unconcerned with personal hygiene, Rasputin would be the last person you would expect to be invited to attend the aristocratic events St. Petersberg’s elite, but he was a singularly unique figure in the then-capital of the Russian Empire.

Employing a legendary force of will — some called Rasputin’s personality hypnotic, while others thought he wielded some dark, sinister magic — Rasputin climbed his way up the social ladder very quickly.

After Rasputin managed to charm some of the extended relations of the ruling Romanov family, he then used these connections to be introduced to the Tsar and Tsarina themselves, beginning a relationship with the Romanovs that would help bring down the Russian Empire and continue to affect events long after Rasputin’s death.

Rasputin Bewitches The Romanovs

Wikimedia CommonsThe Romanov family, last ruling dynasty of the Russia Empire: Tsarina Alexandra, Tsarevich Alexei, and Tsar Nicholas II.

Grigori Rasputin's Son Dmitri Rasputin

When Tsarina Alexandra gave birth to her only son, Alexei, doctors discovered that he was a severe hemophiliac. The Russian people — already hostile to the German-born Tsarina — learned of the new heir’s debilitating condition and blamed the Tsarina for the boy’s affliction, causing the Tsarina considerable mental and emotional distress for the rest of her life.

Unable to find doctors who could cure her son’s condition, or even allieviate his symptoms, the Tsarina put her faith in Rasputin when he stepped forward and promised that he could treat the sickly child’s symptoms through prayer and faith-healing.

To this day, no one knows what Rasputin did to treat Alexei. Whether it was folk medicine, magic, or some sort of placebo effect, it appeared to work. While Alexei’s condition wasn’t cured, Rasputin — and only Rasputin — was able to moderate the boy’s symptoms.

Rasputin’s ability to treat Alexei’s hemophilia made him indispenseable to the Romanovs and Rasputin knew it, exploiting his position to gain greater control over them.

Anxiety Grows Among Russia’s Aristocracy

Wikimedia CommonsA political cartoon mocking Grigori Rasputin and his relationship with the Tsar and Tsarina.

As enthralled as the Romanovs were, the Russian people were not, and soon pinned every calamity on Rasputin’s scheming — and it was largely justified. Rasputin had no idea how to run a country and the advise he gave to the Romanovs was dutifully followed as if it were religious instructions, which usually ended in disaster.

It wasn’t long before rumors were published in the press that Rasputin was the Tsarina’s lover and that he was bewitching the Romanovs with some form of dark magic.

Soon, the Tsar’s nephew-by-marriage, Prince Felix Yusupov, came to the conclusion that only Rasputin’s death would end his control of the Romanovs and restore the legitimacy of the Russian monarchy, which was quickly being destroyed by Rasputin’s actions.

Conspiring with other prominent monarchists — including the Tsar’s cousin, Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, and Vladimir Purishkevich, a deputy in the Duma, Russia’s powerless legislative body — Yusupov set out to kill Rasputin and save the Russian monarchy from collapse.

The Assassination Of Grigori Rasputin

The principal assassins of Grigori Rasputin: Prince Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, and deputy of the Duma Vladimir Purishkevich.

In a memoir written many years after the fact, Yusopov provides a riveting first-hand account of the protracted assassination of Rasputin at his estate in St. Petersberg.

Having arranged to meet together for pastries and wine at his estate, Yusupov picked up Rasputin from his home and brought him to his palace.

To justify eating in the cellar, which had been soundproofed for the occasion, his hidden co-conspirators played records in a closed-off room on the main floor to convince Rasputin that Yusupov’s wife was hosting a small party.

This ruse worked, and the two went down to a furnished cellar to eat, drink, and converse about politics.

Yusupov offered Rasputin pastries and soon Rasputin began gorging himself on cakes that had been laced with cyanide, chosen specifically because they were known to be Rasputin’s favorite so were the most likely to be eaten by him.

Wikimedia CommonsThe cellar of Felix Yusupov’s estate on Moika, in St. Petersburg, Russia, where the murder of Rasputin began.

Worried that the cyanide, which typically kills almost instantly, didn’t seem to be working, Yusupov invited Rasputin to have a glass of Madiera, pouring the wine into one of several glasses that had also been laced with cyanide.

Rasputin declined the glass at first, but Rasputin’s gluttony for wine quickly won out and he drank several glasses of wine from poisoned glasses.

One of Yusupov co-conspirators, a doctor, had prepared each dose of cyanide very carefully to ensure that every one was strong enough to kill not just one but several men.

Yusupov began to panic as Rasputin appeared to consume enough cyanide to kill scores of men while. As Rasputin started to have some difficulty swallowing his wine, Yusupov feigned concern and asked Rasputin if he was feeling ill.

“Yes, my head is heavy and I’ve a burning sensation in my stomach,” Rasputin replied, before saying that more wine would be an adequate cure.

Using a noise upstairs as an opportunity to excuse himself, Yusupov left the cellar to confer with his co-conspirators who were shocked that Rasputin had resisted the effects of the poison.

Though they offered to go down as a group in order to overpower and strangle Rasputin to death, Yusupov decided that he should return alone and shoot Rasputin with a revolver instead.

Upon returning, Yusupov found Rasputin slumping in his chair and struggling to breathe. Soon, however, Rasputin appeared to recover and become more energetic.

Ninara/Wikimedia CommonsA recreation of the cellar of Yusupov’s palace on the night of Rasputin’s assassination.

Fearing that the poison had failed, Yusupov stood up and paced the room to work up the nerve to shoot Rasputin. Rasputin stood up as well and appeared to admire the furnishing that Yusupov had brought down into the cellar.

Seeing Yusupov stare at a crystal crucifix on the wall, Rasputin commented on the cross, then turned away to look at an ornate cabinet on the other side of the room.

Yusupov told Rasputin, “You’d far better look at the crucifix and say a prayer.”

At this, Rasputin turned to Yusupov for several tense moments of silence.

“He came quite close to me and looked me full in the face,” Yusupov recalled. “It was as though he had at last read something in my eyes, something he had not expected to find. I realized that the hour had come. ‘O Lord,’ I prayed, ‘give me the strength to finish it.'”

Yusupov pulled out the revolver and firing one shot, hitting Rasputin in the chest. Rasputin cried out and collapsed onto the floor, where he laid in a growing pool of blood but did not move.

Alerted by the gunshot, Yusupov’s co-conspirators rushed downstairs. The doctor checked for Rasputin’s pulse and found none, confirming that Rasputin was dead, shot close enough to his heart to be immediately fatal.

The Rise and Re-Assassination Of Rasputin

Wikimedia CommonsThe courtyard at the Moika embankment of Yusupov’s estate, where Vladimir Purishkevich shot Rasputin to death after earlier attempts failed to kill him.

Rasputin Grandchildren

The conspirators quickly set about establishing their cover story and separated into two groups, with Yusupov staying at Moika with the Duma deputy, Purishkevich.

Before long, however, Yusupov started feeling uneasy. He excused himself and went back down into the basement to check on Rasputin’s body.

It laid motionless exactly where they had left it, but Yusupov wanted to be sure. He shook the body and didn’t see any signs of life — at first.

Then, Rasputin’s eyelids start to twitch, just before Rasputin opened them. “I then saw both eyes,” Yusupov wrote, “the green eyes of a viper – staring at me with an expression of diabolical hatred.”

Rasputin lunged at Yusupov, snarling like an animal and digging his fingers into Yusupov’s neck. Yusupov was able to fight Rasputin off and push him away. Yusupov ran up the stairs to the first floor, yelling up to Purishkevich, to whom he had earlier given the revolver, “Quick, quick, come down! … He’s still alive!”

WIkimedia CommonsRasputin’s body after it was pulled from the Neva River in St. Petersberg, after news of his death had already started becoming mythologized.

Reaching the landing on the first floor, Purishkevich joined him, revolver in hand. Looking down the steps, they saw Rasputin clawing his way up the stairs on his hands and knees, heading toward a side door leading out into the courtyard.

“This devil who was dying of poison, who had a bullet in his heart, must have been raised from the dead by the powers of evil,” Yusupov wrote. “There was something appalling and monstrous in his diabolical refusal to die.”

Rasputin shoved the door open and ran out into the courtyard. Terrified of what would happen if Rasputin got away and returned to the Tsarina, the two men gave chase.

Dr.bykov/Wikimedia CommonsThe Bolshoi Petrovsky Bridge where Rasputin’s body was dumped into the Neva River.

Purishkevich was the first out the door, and he immediately fired two shots at the fleeing Rasputin. He missed, but then Purishkevich chased down the wounded Rasputin and from just feet away, fired two more shots.

One of the shots struck Rasputin in the head, inflicting a killing blow, and Rasputin collapsed to the ground.

Yusupov had two loyal servants wrap Rasputin’s body in heavy carpets and tied with heavy chains. The conspirators then brought the body to a bridge over the Neva River and dumped it into an unfrozen patch of water below.

The Fallout From Rasputin’s Death And The End Of The Russian Monarchy

Wikimedia CommonsThe supposed site of Grigori Rasputin’s grave, near St. Petersberg, where Tsarina Alexandra had him buried after his assassination.

Shortly before he was shot in Yusupov’s cellar, Rasputin — maybe knowing he was about to die or maybe just boasting — told Yusupov that he would ultimately prevail against his enemies who were plotting to kill him.

“The aristocrats can’t get used to the idea that a humble peasant should be welcome at the Imperial Palace … they are consumed with envy and fury … but I’m not afraid of them. …Disaster will come to anyone who lifts a finger against me.”

Rasputin’s words would be prophetic.

Wikimedia Commons; colorized by Matt LoughreyA colorized portrait of Grigori Rasputin.

In the hours after the assassination, Yusupov was filled with hope. Rasputin’s death was being openly celebrated in the press, violating the emergency censorship restrictions barring mention of the murder, and publicly celebrated in the streets.

“The country was with us, full of confidence in the future,” Yusupov wrote, “The papers published enthusiastic articles, in which they claimed that Rasputin’s death meant the defeat of the powers of evil and held out golden hopes for the future.”

The Tsarina knew that Yusupov, Pavlovich, and Purishkevich had killed Rasputin — even before Rasputin’s body was found, confirming that he was actually dead — but she couldn’t prove it. With their connections to the Imperial family, the Tsarina’s suspicions weren’t enough to prosecute the men. All the Tsarina could do was convince the Tsar to exile the Yusupov and Pavlovich from St. Petersberg.

Wikimedia CommonsStudents and soldiers fighting with police in the streets of St. Petersberg in March 1917, three months after Rasputin’s death.

Yusupov soon grew disillusioned, however, when the restoration that Rasputin’s death was supposed to inspire never materialized.

“For many years,” He realized, “Rasputin had by his intrigues demoralized the better elements in the Government, and had sown skepticism and distrust in the hearts of the people. Nobody wanted to take a decision, for nobody believed that any decision would be of any use.”

Without Rasputin to blame for the mismanagement and failures of the Russian state, the public could only blame the one person who was ultimately responsible for their suffering: Tsar Nicholas II.

When the Russian people finally rose up in March 1917, it would not be in patriotic defense of the Tsar, as Yusupov has anticipated. Instead, it was to reject the very idea that there should be a Tsar at all.

After reading about Grigori Rasputin’s death, read about Rasputin’s daughter, Maria Rapsutin, who became a dancer and a lion tamer in the Untied States. Then, check out these other theories about Rasputin’s place in the royal family.

Grigory Rasputin, a wondering peasant who eventually exerted a powerful influence over Nicholas II and Aleksandra, the last Tsar and Tsarina of Imperial Russia, is one of the most mysterious and dark individuals of Russian history.

Grigory Rasputin was born 10 January 1869 in the small and remote Siberian village of Pokrovskoe. Even as a young man he astonished people; there was talk about him having visions and the ability to heal. According to one legend, one day Rasputin was lying in bed sick when a group of peasants walked in to find out who had stolen a horse. Grigory rose from his bed and pointed at the thief among them. The insulted peasant denied it, and Grigory was beaten. That night, two wary peasants followed the suspect and saw him leading the horse out of his shed and into the forest. Rasputin gained a reputation as a visionary, although some were scared of the boy and thought he was possessed by the devil. It was a time and place where all possible magic and heeling powers were a way of life. Grigory himself thought that he was taken over by a higher force. He was also a drunk, got into fights and harassed women. He got married when he was around twenty and had four children.

A visit to a monastery in Verhoturye changed him; it was his first encounter with a ritual form of religion. He ended up staying there for months. Rasputin then left his home to become a ‘strannik,’ a pilgrim or wonderer. His journey took him as far as Greece and Jerusalem. He sometimes walked for days without eating or stopping; he didn’t wash or even touch his body for months and wore shackles to increase the hardship of his journey. It is believed that during his travels he may have encountered a secret sect called the ‘hlysty.’ They organized a particular kind of worship in which there were no priests; in one part of the service they sang and prayed and became almost drunk by spinning; in the other part they indulged in flagellation and orgiastic sex. This type of worship, they thought, would bring them closer to God. ‘Driving out sin with sin’ was the concept that Rasputin later adopted. After his travels of more than two years he returned to his village of Pokrovskoe. The locals saw a change in him; he was perceived by some to have a luminescent religious essence and was even called a ‘staryets’, a wondering holy man, by others.

Even before his arrival in St. Petersburg in 1903, the city was agog with mysticism and aristocrats were obsessed with anything occult. Rasputin met Bishop Theophan, who was at first shocked by Rasputin’s dirty look and strong smell, but he was nonetheless mesmerized by the ‘holy’ man and shortly introduced him to the Montenegrin princesses, Militsa and Anastasia, who also fell under his spell. He was then introduced by the sisters to Nicholas II and Aleksandra (the Tsar and Tsarina). Aleksandra was impressed by him straight away and he became a regular visitor to the palace; she spent hours talking to him about religion. Rasputin would tell her that she and the Tsar needed to be closer to their people, that they should see him more often and trust him, because he would not betray them, to him they were equal to God, and he would always tell them the truth, not like the ministers, who don’t care about people and their tears. These kinds of words touched Aleksandra deeply; she absolutely believed that he was sent to the royal family by God, to protect the dynasty. To her, Rasputin was the answer to their hopes and prayers. The Tsar and Tsarina shared with him their concerns and worries, most importantly, over their son Aleksey’s (the only male heir to the throne) health. He suffered from hemophilia. Rasputin was the only one who was able to actually help their son, how he did it will always remain a mystery, but Aleksey got better. The palace governor wrote in his memoirs: “From the first time that Rasputin appeared at the heir’s bed, he got better. Everybody at court remembers the episode in Spala, when no doctor could help the suffering and moaning child, but as soon as a telegram was sent to Rasputin, and they received an answer that the boy would not die, his pain eased straight away.” Everyone who met Rasputin remarked on his eyes and how hypnotic they were. Elena Dzhanumova wrote in her diary: “What eyes he has! You cannot endure his gaze for long. There is something difficult in him, it is like you can feel the physical pressure, even though his eyes sometimes glow with kindness, but how cruel can they be and how frightful in anger…”

Rasputin Movie

Nicholas also trusted Rasputin. He became his advisor whose one word was enough to place an unknown person as a minister at court. But Nicholas sometimes decided government questions of a higher scale by himself. Rasputin was strongly against the First World War (1914 - 1918) and tried to convince the Tsar to make peace with Germany, but Nicholas held his ground and took Russia to war, which was a disaster for his country, with more than four million Russians loosing their lives.

Rasputin lived in an apartment on Gorohovaya Street. There, peasants and aristocrats came to visit him. Peasants and the city’s poor worshiped Rasputin and believed in his holiness and sometimes asked for help and money, and aristocrats, knowing his influence at court, visited him only to gain his favor and use it for their career growth or just because it was ‘fashionable.’ He also seduced women with his charm, preached and entertained. It was rumored that he organized his own sect performing religious sex rituals. Many reports of Rasputin’s unholy behavior reached Nicholas. But he dismissed these reports of Rasputin’s outings to bathhouses, beatings and violent sex with society women and prostitutes. He laughed them off by saying “the holy are always slandered.” Even Bishop Theophan tried to tell Nicholas to distance himself from Rasputin, but for this he was relieved of his post and banished.

In December 1916 Rasputin sent a letter to Nicholas about his own death: “I

feel that I shall leave life before January 1st. I wish to make known to the Russian

people, to Papa (the Tsar), to the Russian Mother (the Tsarina) and to the Children what they must understand. If I am killed by common assassins, and especially by my brothers the Russian peasants, you, the Tsar of Russia, will have nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years. But if I am murdered by boyars, nobles, and if they shed my blood, their hands will remain soiled with my blood for twenty-five years and they will leave Russia. Brothers will kill brothers, and they will kill each other and hate each other, and for twenty-five years there will be no peace in the country. The Tsar of the land of Russia, if you hear the sound of the bell which will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your relations who have wrought my death, then none of your children will remain alive for more than two years. And if they do, they will beg for death as they will see the defeat of Russia, see the Antichrist coming, plague, poverty, destroyed churches, and desecrated sanctuaries where everyone is dead. The Russian Tsar, you will be killed by the Russian people and the people will be cursed and will serve as the devil’s weapon killing each other everywhere. Three times for 25 years they will destroy the Russian people and the orthodox faith and the Russian land will die. I shall be killed. I am no longer among the living. Pray, pray, be strong, and think of your blessed family. ”

Rasputin was mostly hated among the nobles, especially Nicholas’s family members. He appeared to them as a drunk, a dirty man who infiltrated his way into the royal family, who appointed and dismissed ministers, and for over ten years was the central figure in Petersburg’s scandal news and at the same time ruled over the Tsar in some strange way. Prince Felix Yusupov (husband of the Tsar’s niece Irina) wanted him dead and wasn’t alone. The Tsar’s cousin, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, and Vladimir Purishkevich, a member of parliament wished to get rid of Rasputin and his demonic influence. The three invited Rasputin to the Yusupov Palace on December 30, 1916 to meet the Tsar’s niece. While waiting for her to appear, Rasputin was offered wine and his favorite cakes laced with a tremendous amount of cyanide. Hours went by and the poison did not affect Rasputin. Dismay and fear came over Yusupov who reached for his gun and shot Rasputin. Everyone was sure that it was the end of him, but miraculously he staggered out of the palace. Vladimir Purishkevich ran after Rasputin and shot him again in the back, but it was only when they threw his body into the Neva River that he died. Just ten weeks after his death, the Romanov dynasty was overthrown during the Russian Revolution of 1917. Less than two years later, Nicholas and his entire family were executed.

The topic of Rasputin to this day comes up in literature, cinema and even music. Seventies pop group Boney M had a hit single “Rasputin” with the memorable lyrics “Rah, rah, Rasputin, lover of the Russian Queen.” More recently in Fox’s animated film, “Anastasia,” Rasputin is portrayed as the traitor monk who casts a curse on the Romanov family. Rasputin aroused different feelings in the people who surrounded him. Some felt fear, others deep veneration, and still others hatred - and even now the attitude towards him is ambiguous. He’s either a holy miracle worker or a charlatan.

For more information on Russia's arguably most charismatic figure check RT's documentary .

Written by Maria Aprelenko, RT